It’s been a busy year for Ulysses-fans, with the book getting a lot of attention on the internet through reading groups like our own, Twitter members posting quotes and page summaries, but especially through the ambitious adaptation being undertaken at Ulysses “Seen,” which has received a bonanza of media attention due to a recent controversy with Apple over the iPad version. Robert Berry, the artist heading the Ulysses “Seen” team, was gracious enough to take some time away from the drawing board to answer a few questions about his project.

Berry’s portrait of a “Disapproving Joyce”:

JS: Let’s start with some general stuff (I realize you’ve discussed this elsewhere, including on your own blog at the site, but it’s worth rehashing for people who might not know about your project): Why Ulysses? Is there something about this novel in particular that you think lends itself to the kind of adaptation you’re doing?

RB: Some years back, while first noodling around with the idea of working in comics and graphic novels, another cartoonist and I attended a BloomsDay reading here in Philadelphia. I’d read the novel before then of course, so I was there more as a celebrant than a novice, but this was first time I’d been to something like this. Hearing passages from novel read aloud, particularly to a crowd, is a completely different experience than tackling it on your own. When it’s good, when the reader is really getting it, you can see it on the faces of everyone in the crowd and you can see that they’re getting it too. It’s like theatre and everyone’s just standing around in the twisting turning halls of Joyce’s language and wit.

But it’s not theatre, of course. It’s novel, an intentionally very complex novel, with a very bad reputation as being “difficult”. Unlike theatre, novels have a very one-on-one relationship with the reader; they’re something you can carry with you, pause to think about and unravel at your own pace. Something to stage in your own imagination.

I wanted to make a comic that could give people that same kind of one-on-one relationship with the text but could also give them that same kind of stage direction you get out of the theatre combined with an easy reference guide to what’s going on. A way to “see” the novel as you’re reading or hearing it.

JS: Speaking of which: Why a comic book? (Is that the term we’re using?: certainly Joyce considered his work a “comedy,” in the old, Dantean sense of the word, but what you’re doing isn’t exactly a book, is it?) And why publish online, panel-by-panel?

RB: Over a few pints of Guinness at the pub on that same BloomsDay, my friend and I got into a discussion of how comics was the only media that could do a faithful adaptation of Joyce’s novel. Theatre and film don’t work because they happen in the real time of the audience. The reading experience works in a completely different way with comics and text. Comics have a linear flow, one image following another, but that line has more freedom, more plasticity, in how it relates to time.

Comics on-line, or on the iPad, have an even greater plasticity than they do in print. What we’re able to do on-line is use a comic panel to freeze a moment in reading Ulysses and allow the reader to jump “behind the page” to look at annotations from the novel or ask questions about what is going on and who some of the characters are. The comic itself serves as a kind of guide for all the external materials, discussions and concepts one might get from reading the novel in a classroom environment.

And Joyce is just waaaay funnier than Dante was.

JS: I don’t know, I bet the Inferno was pretty friggin’ hilarious when it first came out…

RB: It definitely raised more than a few laughs at the time, but it’s a bit more of a “had to be there” kinda humor I think…

JS: Tell me a little bit about your process: how do you go about deciding what a given “page” is going to look like, and then how do you achieve your vision? What’s the timeframe like: how long does a given page take, start-to-finish?

RB: The process is pretty unique in that I’ve never encountered anyone working on something like this, so we sort of took a little time to figure out the method. It all begins with the novel, of course. I have a replica of the 1922 edition, our sole source for the text, that I’ve color-coded with about six different highlighter markers to indicate the differences between action, spoken dialogue, internal monologue, etc.

The first page of Berry’s working copy of Ulysses:

Since each episode (or chapter) of Joyce’s novel presents new viewpoints and narrative styles, my four partners and I get together and talk over beers about the episode we’re doing next. Right now, that’s “Calypso”. This helps give me a set of guidelines to follow, a kind of a plan of what other people look for in a specific chapter. After that, I step away from the group for a while and make a set of storyboards, a rough comic, that includes all the original text. The goal at this stage is to pace and stage the flow of words as a director of a film might, looking for the beats implied by the language and giving just enough information so that readers can see who’s speaking as well as their relationship in space. This is a particularly complex stage, particularly when dealing with work as complex as Ulysses, so I tend to do this part on my own and don’t let anyone see it until I know I’ve made the right choices. It’s the guts of the comic.

After that is done, the storyboards go back to my partners for edits and a bit more discussion. It’s often surprising to see how differently each of us view the novel once it’s been drawn and there are occasional important changes that occur during this stage. From here, the work goes back to myself and our production designer Josh Levitas. Josh hand-letters and sets up the page files into what we call “floorplans”. This allows me to make drawings on hand-lettered pages around the text in accordance with my original storyboards. I think it keeps a freshness and a liveliness to the drawing that was lost in earlier versions in which we lettered with the computer over existing drawings. For the next chapter Josh is doing a lot of the set design as well, making drawings of objects in Mr Bloom’s house that we’ll see again much later in the novel.

In the meantime Mike Barsanti, our resident Joycehead, starts working on the Readers’ Guide entries for each page. He explains some of the major themes and issues in the novel, gives some Joycean anecdotes and tries to show links to other related topics and discussions. It’s an area of the project that I have very little to do with but am probably most proud of.

The goal here in all of our work is open up the world of the novel using comics and the internet, to make it a bit less daunting and to show how it connects to today’s readers as something more than just an English Literature merit badge. It’s a complex novel, certainly, but that complexity, once they’ve started to crack it, brings readers back again and again. It’s what makes it the most difficult book you’ll want to read many times.

JS: I see you’re doing the “Calypso” episode second, rather than “Nestor”: that makes sense to me, but would you care to comment on the decision?

RB: I decided pretty early on that I wanted to go chronologically through the first six episodes of the novel. They’ll still be sorted and numbered according to their original order, so “Calypso”, though it appears next, will still be called episode number 4. I made the decision when I was first thinking about how the web and the iPad are much more flexible platforms for annotation. It seems to me that the comparison between these two chapters is a useful learning guide for first time readers so we wanted to step up that process just a bit. But the main reason for it is that I’m going to do “Nestor” and “Lotus Eaters” simultaneously next year, shuffling their pages together to show the chronological relationship between Stephen’s day and Mr Bloom’s. I’ve already laid that chronology out and, believe me, it’s a great example of comics is such a good format for adapting Joyce.

Plus, I was a bit anxious to get to draw Bloom. If I’d have gone with the strict order of the novel that wouldn’t be happening for another year or two.

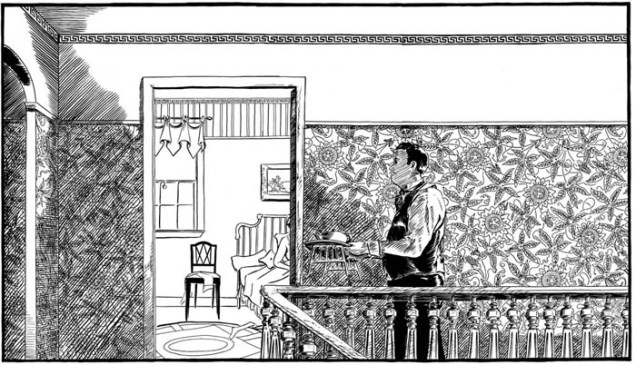

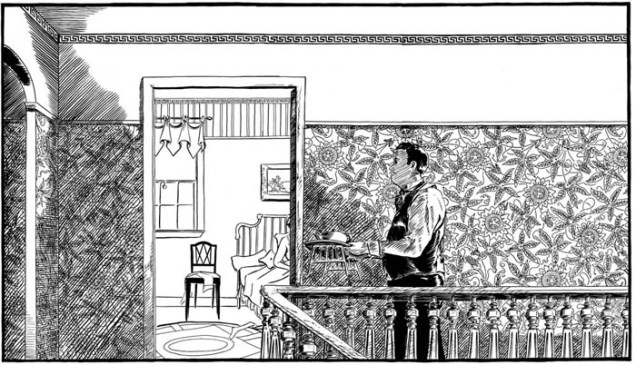

A sample of the forthcoming adaptation of “Calypso”:

JS: Are there any moments/panels that gave you particular trouble, in terms of interpretation/adaptation?

RB: All of the internal monologue presents problems when you start it. As an illustrator you need to separate out a certain voice for each character and how they see the world. Mr Bloom’s inner mind can’t rely on the same visual devices as Stephen’s does and both have to be distinctly separate from the voice of the omniscient narrator. I could’ve cheated a bit, used different font styles to represent this, but I think that’s kind of a cheap parlor trick in comics and, with so many distinct voices in Ulysses, bound to be confusing later.

But establishing an order for how to slip into the imagination of each character is probably the hardest bit. I think you’ll notice it quite a bit in “Calypso” that Bloom doesn’t dream about the world in the same hard imagery and weight of words that Stephen does.

JS: What are you looking forward to most, in terms of the coming chapters? Is there any particular moment/line that you can’t wait to illustrate?

RB: Off the top of my head it’s that scene in “Lestrygonians” when Bloom has the memory of the seedcake being passed into his mouth and notices the two flies, buzzing, stuck on the window. To me, that’s a very poetic combination of imagery and text, all of what comics can do better than most other narrative mediums.

JS: Wow… that’s pretty much my favorite moment in the whole book.

A big thank you to Rob and his collaborators at Ulysses “Seen.” Rob will be joining us on our reading, and will post his thoughts about the episodes that he has adapted so far in the coming weeks.