How do you “see” a novel? When you read, are you giving faces, costumes, and audible voices to the characters? Is the narrative played out in your head as your eyes scan the words? Or do you concentrate on the deeper levels of meaning, turning the characters into vehicles that exist only to convey ideas or act as a mouthpiece for the author’s worldview? I think it’s a fascinating line of inquiry, and one which I have long been obsessed with. How do we read?

For me, since the earliest books I can remember reading were lushly illustrated fairy tales, collections of myths, and dinosaur books, the visual elements has been inseparable from the narrative element of reading. When I eventually graduated to books without pictures, I would devour the cover images, looking for any kind of clue as to what the characters might look like. Often, I simply resorted to elaborately visualizing them in my head, creating details where they were lacking and quickly growing frustrated with authors who refused to acknowledge this lust for visual detail in their readers. Which, I know, might make me one in a small minority.

All of these issues were brought to the fore when I began my project to illustrate Moby-Dick. Once I began, I marveled at how inconsistent my own visualizations were but after careful thought, this began to make sense. If I think back to how my wife looked last night walking out of the airport concourse after her trip, I see her complete figure, largely in silhouette, but whole and complete. If I think back to how she looked when I showed her last night’s Moby-Dick illustration, I see the top of her head mostly, her short glossy black hair shining as she peers down at the page, and perhaps I see a bit of hands as she holds the illustration. Gone is just about everything below the torso. It just doesn’t exist because it doesn’t have to.

One of the greatest challenges in illustrating Moby-Dick has been creating images of characters that I knew would appear again and again and again, in drastically different situations, affected in all sorts of ways by what was currently happening in the narrative. In casting these whale men and mates and harpooneers as almost ship-like constructs, this problem became magnified. How to show emotion? How to demonstrate action? How to show them changing? In this sense, relying on the illustrations to be highly symbolic has been crucial.

So, when it came to the three mates, Starbuck, Stubb and Flask, I knew that I wanted to capture something unique, instantly recognizable, and deeply symbolic (at least to me) for each. I knew I would have ample opportunity to revisit them again and again throughout this project, but as is the case with any drama, first appearances mean the most. Fortunately, Melville is generous with his prose, and gives enough descriptive detail to get even the most uninterested reader started on a good visualization. First, Starbuck…

The chief mate of the Pequod was Starbuck, a native of Nantucket, and a Quaker by descent. He was a long, earnest man, and though born on an icy coast, seemed well adapted to endure hot latitudes, his flesh being hard as twice-baked biscuit. Transported to the Indies, his live blood would not spoil like bottled ale. He must have been born in some time of general drought and famine, or upon one of those fast days for which his state is famous. Only some thirty arid summers had he seen; those summers had dried up all his physical superfluousness. But this, his thinness, so to speak, seemed no more the token of wasting anxieties and cares, than it seemed the indication of any bodily blight. It was merely the condensation of the man. He was by no means ill-looking; quite the contrary. His pure tight skin was an excellent fit; and closely wrapped up in it, and embalmed with inner health and strength, like a revivified Egyptian, this Starbuck seemed prepared to endure for long ages to come, and to endure always, as now; for be it Polar snow or torrid sun, like a patent chronometer, his interior vitality was warranted to do well in all climates. Looking into his eyes, you seemed to see there the yet lingering images of those thousand-fold perils he had calmly confronted through life. A staid, steadfast man…

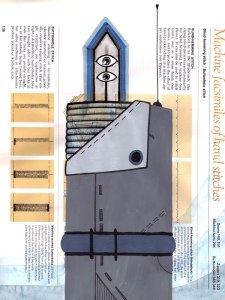

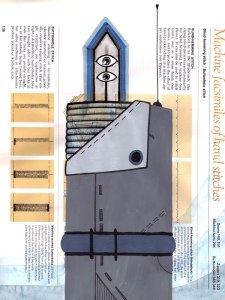

Those who have read the novel before know that Starbuck is the one man most qualified to stand against Ahab, to block his mad, monomaniacal mission and thus save the lives of everyone on board the Pequod, and yet he fails repeatedly to do so. Starbuck is no coward, yet he seems to lack the vision necessary to see beyond his narrow role as first mate, as Ahab’s subordinate, and as a crucial cog in the orderly running of the ship. While Starbuck almost takes that final step, and even contemplates murdering Ahab, he stops short. Not only does he lack the support of the crew, he feels bound by his duty to the ship and to Ahab and sees breaking those obligations as perhaps a crime worse than the mad pursuit of what he feels is a dumb beast. Starbuck was, for me, the easiest to see, and the easiest to illustrate. Beginning with his “long, earnest” lines and his almost perfect subservience to Ahab, I saw Starbuck as Ahab’s sword. A lean blade of a man, there to further the captain’s will. A perfectly forged tool, balanced, lethally effective, and yet lacking in any real independence. I gave Starbuck the sober grays and blues of the stormy New England sea, an odd radio antenna to signify his near total control by Ahab, and two forward looking eyes on his blade-like face to demonstrate his blindness to alternatives.

Stubb was more complex, and more personal. To me, Stubb’s near constant joking seemed something that masks a deep fear, a terror of accepting reality. At his heart, I have always thought of Stubb as little more than a coward. Melville writes…

Stubb was the second mate. He was a native of Cape Cod; and hence, according to local usage, was called a Cape-Cod-man. A happy-go-lucky; neither craven nor valiant; taking perils as they came with an indifferent air; and while engaged in the most imminent crisis of the chase, toiling away, calm and collected as a journeyman joiner engaged for the year. Good-humored, easy, and careless, he presided over his whale-boat as if the most deadly encounter were but a dinner, and his crew all invited guests. He was as particular about the comfortable arrangement of his part of the boat, as an old stage-driver is about the snugness of his box. When close to the whale, in the very death-lock of the fight, he handled his unpitying lance coolly and off-handedly, as a whistling tinker his hammer. He would hum over his old rigadig tunes while flank and flank with the most exasperated monster. Long usage had, for this Stubb, converted the jaws of death into an easy chair. What he thought of death itself, there is no telling. Whether he ever thought of it at all, might be a question; but, if he ever did chance to cast his mind that way after a comfortable dinner, no doubt, like a good sailor, he took it to be a sort of call of the watch to tumble aloft, and bestir themselves there, about something which he would find out when he obeyed the order, and not sooner.

What, perhaps, with other things, made Stubb such an easygoing, unfearing man, so cheerily trudging off with the burden of life in a world full of grave peddlers, all bowed to the ground with their packs; what helped to bring about that almost impious good-humor of his; that thing must have been his pipe. For, like his nose, his short, black little pipe was one of the regular features of his face. You would almost as soon have expected him to turn out of his bunk without his nose as without his pipe.

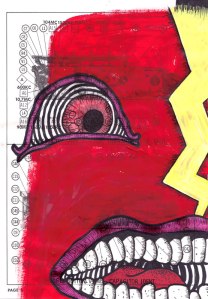

True, there is little there, or even in the remainder of the novel, to paint Stubb as a coward but it is a feeling I have never been able to lose. Stubb’s stubborn refusal to treat matters of life and death as anything other than a joke has never seemed to me to be carefree or valiant. Rather, it is an unwillingness to accept and to engage with the realities of a dangerous life. Nothing communicates cowardice better than the color yellow, so Stubb comes complete with yellow streaks down his head and back. The pipe is there too, of course, as it must be. And it is great fun to draw. But at all times, Stubb hides the yellow cowardice behind him out of sight if he can. He is one-eyed, since he can only see the world in one way, as a joke.

Flask is perhaps the least developed and most one dimensional of the mates. A small, furious man with a monstrous yet hilarious temper. Melville describes him thus…

The third mate was Flask, a native of Tisbury, in Martha’s Vineyard. A short, stout, ruddy young fellow, very pugnacious concerning whales, who somehow seemed to think that the great Leviathans had personally and hereditarily affronted him; and therefore it was a sort of point of honor with him, to destroy them whenever encountered. So utterly lost was he to all sense of reverence for the many marvels of their majestic bulk and mystic ways; and so dead to anything like an apprehension of any possible danger from encountering them; that in his poor opinion, the wondrous whale was but a species of magnified mouse, or at least water-rat, requiring only a little circumvention and some small application of time and trouble in order to kill and boil. This ignorant, unconscious fearlessness of his made him a little waggish in the matter of whales; he followed these fish for the fun of it; and a three years’ voyage round Cape Horn was only a jolly joke that lasted that length of time. As a carpenter’s nails are divided into wrought nails and cut nails; so mankind may be similarly divided. Little Flask was one of the wrought ones; made to clinch tight and last long. They called him King-Post on board of the Pequod; because, in form, he could be well likened to the short, square timber known by that name in Arctic whalers; and which by the means of many radiating side timbers inserted in it, served to brace the ship against the icy concussions of those battering seas.

Notice that Flask, too, is shown to be something of a jokester. Yet his temper, his hatred of the whales, his view of the great beasts as something that had “personally and hereditarily affronted him” casts his humor in a vastly different light than Stubb’s. Flask lacks some of the details of the first two mates, being depicted as short, stout, ruddy and pugnacious. To me though, these words conveyed magnitudes and Flask ended up being short, stout, hopefully ruddy, and with great waves of flaming anger radiating from his tiny musket ball-shaped skull…

Clad in a greatcoat the color of dried blood, Flask’s great eyes stare furiously forward, searching for whales to summarily slaughter. I chose this piece of found paper very careful as well for the heading “The parts of a pattern.” After all, what else are the mates, if not pieces of the pattern of the novel? In spite of their humanity, each functions more as a symbol, almost a set piece, designed to define or contradict Ahab. Their roles, their lives, are unimportant. How they function in the hands of Ahab, whether or not they further his mad schemes or obstruct them in some way, that is all that counts. The pieces are slowly falling into place for the great voyage.

(I had originally meant to post this almost a week and a half ago. Numerous daily life obligations, technical difficulties, and everything else under the sun conspired to keep me away. I hope to remedy that this week with 3 or 4 more posts, if you can tolerate that. Also, Daryl, I owe you an email which will arrive no later than tomorrow. I don’t expect to be home until around 9 this evening, and then I need to finish today’s illustration. As Melville so succinctly put it, “Oh, time, strength, cash and patience!”)