There is a lot going on in this week’s reading, and there were two big things I especially wanted to touch on, though I feel like I could write about a hundred pages on this section alone.

The first thing answers the question I posed last week: Why did Levin spend 12% of the book on the film transcript? It turns out that it’s vital to this big ambitious project Triple-J is doing that Belt has signed on to help with. Rob commented on my post last week that he was confused by the stark difference in writing style between what we’ve seen of Triple-J’s work before and the style of the transcript. Rob went on to say that he couldn’t see how Trip was the author of the descriptions. And, well, it seems very likely he’s right. It’s not confirmed yet, but by this week’s reading milestone, Belt is on the cusp of signing the contract to write the descriptions, and unless something goes sideways in the meeting with Jonboat and the notary, it seems likely that this transcript is Belt’s work (he received the film and not the transcript, recall). And suddenly the transcript is relevant not only because it deals with cures and with this heretofore minor character but because it is Belt’s work. Further, it becomes important not merely as documentation of cure abuse (indeed sort of explicitly not as documentation of abuse as abuse) but of Belt’s big artistic project — it is intentionally an ekphrasis designed as part of the art itself to aid in distribution that Trip thinks will further his project.

So that’s that. I could say a lot more about Trip’s project and the conversations about it in this week’s reading. Books that talk about art really ring my cherries, so normally I would latch onto this bit a lot harder. But instead, I’m going to turn to something probably more trivial and the rabbit hole it sent me down.

Back in week one, I focused on little things like punctuation and the strange dots separating subsections of the book. And during the Zoom book club after which Levin engaged in a delightful conversation with the handful of attendees, the question of these dots came up. Levin declined to explain the significance of the dots or their slightly-off spacing, I presume to do us the kindness of not spoiling what became suddenly clear in this week’s reading.

Belt describes the scene of his arrival at Jonboat’s compound 25 years earlier, ending with the spitting out of gum wads by three of Jonboat’s pals. This section is followed on page 501 by the three dots and a new section whose (thats) opening describes Belt’s recent arrival at the compound and which I’ll quote:

A quarter-century later, when I showed up for brunch, the spat gum was still there, in the middle of the cul-de-sac, three black near-circular stains on the pavement before which I paused, overcome by a memory, a long-lost memory: first sensory, then narrative: a breathtaking recollection of my mother. Of my mother in profile. My mother’s left temple. She’d had a trio of birthmarks (that’s what she’d called them — my father’d called them beauty spots, I’d called them freckles) that you could see only one of unless she tied her hair back. Like those gum stains, her birthmarks were arrayed in such a way that, were you to connect them — as I (I suddenly remembered) once had; I’d used an eyebrow pencil — they’d form an obtuse, scalene triangle.

The dots do signify something! I lacked the memory of basic geometry to call the triangle formed by the dots a scalene triangle when I wrote about them, but I recalled enough to know that they did not form an isosceles triangle. This visual correspondence to a thing in the book connecting past to present and Belt to mother was thrilling to me.

It also made all kinds of sirens go off. I had never read Swann’s Way (the opening book of Proust’s Remembrance of Things Past, or In Search of Lost Time depending on the translation) until the last year or two. Honestly, I found it a bit of a snooze, even if some of the opening bits at least were lyrical and evocative. I don’t remember much of it (heh), but something about the setup Levin gives us here brought the “Overture” chapter of Proust’s book right to mind. I re-skimmed that opening chapter alongside my manic annotations of this portion of Bubblegum and found a number of things that feel an awfully lot like correspondences, or very happy coincidences. Page numbers to Proust’s book given below refer to this edition.

I do want to be careful to say that I’m ascribing no intent to Levin here. Maybe he’s intentionally looking back to Proust and maybe he’s not. Either way, I went back to Proust, and reading the two together enriched the reading of both books for me. And this is a marvel. This sort of thing is one of the things I love most about reading.

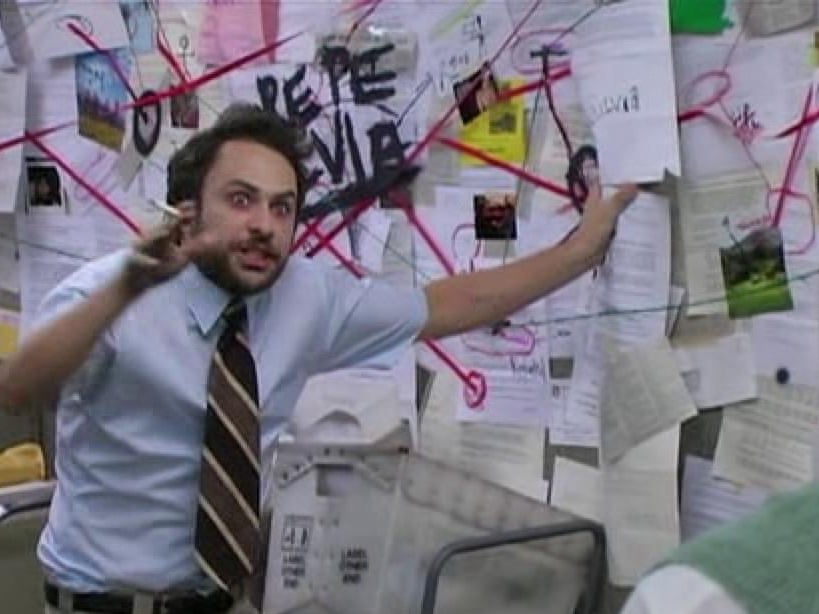

I feel a little bit like somebody hunting down conspiracy theories when I do this sort of inter-textual comparison, but here goes anyway, more a list of things I noticed than any sort of analysis.

The most obvious correspondence is that we’re dealing here with childhood memories of mothers. Proust’s young Marcel longed for his mother’s goodnight kisses and has what started as a sort of traumatic experience of being denied these kisses while company was visiting that then turned into a lovely evening of motherly tenderness. Belt too recalls a tender, intimate moment with his mother in which she allows him to connect her birthmarks with an eyebrow pencil.

But more than that, both books show us sudden recollections many years later, provoked by very specific vaguely culinary things — in Belt’s case, it’s the titular bubblegum, in Marcel’s a petite madeleine dipped in tea. And in both, the memory begins as a sensory memory and shifts to a more narrative one.

This week’s reading opens with Belt waking and talking to his pillow. In the opening of Swann’s Way, Marcel writes about waking and drowsing in and out of dreams and memories. He mentions his pillow (a weak connection and an obvious object to mention in a passage about sleeping and waking, I know; it’s not nearly as significant as Belt’s conversation with his own pillow).

Marcel tells us about a magic lantern he had as a child that when placed upon his lamp projected scenes he could flip through and enjoy but which also left him feeling sort of uncomfortable because of how bathing the room in these scenes disrupts the familiar context of his bedroom. Belt watches Trip’s series of scenes and feels, he says, compromised because he had enjoyed parts of the film (the cuteness of the cures) “independent of its context, independent of its cause” (494).

Marcel’s grandmother is a bit of a hard-ass. So is Belt’s.

Marcel and Belt too share at times a discursiveness and obsessiveness of thought. But what writerly character doesn’t?

Young Marcel upsets his mother’s expectations of him by first sending an unsolicited note to her and then lurking in the hall only to be caught. He fears that he has “committed a sin so deadly that [he] expected to be banished from the household” (40). But his father shows some unexpected generosity and tells Mamma to stay with him for the night — “a far greater concession than I could ever have won as the reward of a good deed” (40). Belt’s sin too seems bigger to him perhaps than to us. He has failed to watch Trip’s film and twists himself up about it a little obsessively, as Marcel does about his sin. But Belt too is rewarded unexpectedly in spite of his sin, with a very lucrative contract.

Both young men give consideration to the impact of their actions on their mothers, whose approval they seek. Marcel’s bedtime indiscretion leaves him feeling that he “had with an impious and secret finger traced a first wrinkle upon her soul and brought out a first white hair on her head” (41). This called to mind for me Belt’s concern for his mother’s feelings about his disappointment in various museum exhibits and his urge to protect her from his disillusionment.

When describing his mother’s reading aloud, Marcel says the following on page 46:

She found, to tackle them in the required tone, the warmth of feeling which pre-existed and dictated them, but which is not to be found in the words themselves, and by this means she smoothed away, as she read, any harshness or discordance in the tenses of verbs, endowing the imperfect and the preterite with all the sweetness to be found in generosity, all the melancholy to be found in love, guiding the sentence that was drawing to a close towards the one that was about to begin, now hastening, now slackening the pace of the syllables so as to bring them, despite their differences of quantity, into a uniform rhythm, and breathing into this quite ordinary prose a kind of emotional life and continuity.

Compare to Belt describing his representation of monologues people like Chad-Kyle and Lotta aim at him:

I’ve reported Lotta saying what she said the first way rather than reporting it the second or third way not because the first way seems to me to more accurately depict what Lotta said or who Lotta is than do the second or third way, but because all three seem to me to be highly and equally accurate depictions, and to my ear at least, the first way sounds better (it’s more in keeping with the rhythm of the paragraph from which I’ve excerpted it, and it comes across more clearly with regard to pronouns) than the second or third way.

There’s a similar sensibility here, no?

I’m beginning to run out of yarn and pushpins to hold up all these probably ridiculous associations I’m sticking up on the wall, though I jotted down a few more. I’ll leave you with one more. In Swann’s Way, we read this interesting bit on page 47:

I feel that there is much to be said for the Celtic belief that the souls of those whom we have lost are held captive in some inferior being, in an animal, in a plant, in some inanimate object, and thus effectively lost to us until the day (which to many never comes) when we happen to pass by the tree or to obtain possession of the object which forms their prison. Then they start and tremble, they call us by our name, and as soon as we have recognized their voice the spell is broken. Delivered by us, they have overcome death and return to share our life.

And so it is with our own past. It is a labour in vain to attempt to recapture it: all the efforts of our intellect must prove futile. The past is hidden somewhere outside the realm, beyond the reach of intellect, in some material object (in the sensation which that material object will give us) of which we have no inkling. And it depends on chance whether or not we come upon this object before we ourselves must die.

It, again, is not my intent to insist that Bubblegum is informed by Proust’s book (intentionally or not), but this certainly seems sort of relevant, doesn’t it?

The connections to Proust are very observant of you and interesting. I cannot speak to that, so I’ll focus on the first part.

♦

♦ ♦

It was nice to see mentioned my earlier comment about the “transcript’s” authorship, so thanks for that.

♦

♦ ♦

When I read about the three splotches of gum on the road, I immediately said “a-ha!” with respect to the section symbol. But then the author continues to strengthen that connection with obviously more meaningful memories about three marks on his mom’s neck.

There are three marks on the cover of the book too. As an e-reader, I have only seen the cover in a relatively un-detailed way. As a result, for a while I thought that the sphere on the cover showed an abstract reflection of a swingset! In that view, there are three swing seats and three lines for their supports, and the squiggly things at left are a tree. (Cover of book: https://images1.penguinrandomhouse.com/cover/9780385544962 )

Of course, it is clear to me now that the sphere is the thing from which the botimal emerges, and those three marks are claws breaking through, but I still think it could also reflect the swingset theme. The sphere looks like it is reflecting an image, at least on a smallish digital cover. I would have seen claws and their shadows on Day One if I had the physical book, and I’m sure you all did. I interpreted the large shadow as a person hovering over the sphere.

It seems then that the three dots of the section break refer to all of these things that are in threes—these claws, the bubblegum splotches, his mother’s birthmark(s).

♦

♦ ♦

I am tired of both Triple J and extended discussion of cures, so this is now most of two weeks’ reading that I haven’t enjoyed too much. If I didn’t feel that the book would now re-center Belt, going into the “home stretch”, I would probably put it down (but I’m also too far in to give up).

Which raises a simple question I have for others: do you dislike Triple J as much as me? Is he written to be disliked? He is a self-involved privileged kid who can’t stop talking about himself. Fondajane, who should know better, seems to want to ensure he never feels too hurt or upset by anything. Despite her occasional critical feedback about his behavior, she comes off as mostly enabling.

He assaulted Our Protagonist and was probably only sorry he did because the person he beat up turned out to be his “hero”. I’m not a fan of Belt continuing to act mostly supplicant-ly toward Triple J. With 100k at stake now, I can understand that sort of behavior going forward, but he’s been doing it the whole time.

In fact, it makes me think less of Belt, the adult. I must confess that I am invested in Belt’s life, and I’d likely prefer a slightly different book that tracked more like the first third of Bubblegum (Belt’s past, his relationships (is Lotta coming back?—I hope so), etc). OK this is a pretty long comment and I can’t worry about editing it any more.

I did not see a swingset, but absolutely do now–the shadow as well. Intentional or not, I think it’s cool.

I do not dislike Triple-J. I feel like he is well-intentioned but foolish or perhaps immature is more correct. From his papers to his grandiose designs, he seems like he was basically told that the sky’s the limit for him (and if your dad is a super rich astronaut, i guess it is). He seems to keep having good ideas and then reality crashes down on him (he sucks at chemistry, he’s not a great writer). He also only seems to have Burroughs there to teach him what to do and how to act.

Fondajane is definitely enabling him,

But his new aim of trying to get people to do something different with cures seems like he is really trying to do something for humanity–however misguided it may be.

The assault for sure is not great. My consolation is that he was standing up for his Yachts and he could have easily done a lot worse. (small comfort I know, but i look for the best in people).

As for Belt, he seems pretty subservient in general. And since Trip clearly has never been told to shut up once he starts going, it would be hard to imagine Belt saying, hey dude, pause for a second. I know I would have a hard time interrupting Trip with Fondajane sitting right there.

Oh, I hadn’t put together the marks on the cover. I had recognized it as being an ovum with a little claw coming out, but then I pretty quickly pulled the cover off the book and set it aside. I do occasionally pick it up and sniff it. But now that you mention it, I do see swings and a tree. And the claws poke through in the triangular configuration. What a great observation.

I can’t decide whether I like Triple-J or not. I think mostly I don’t like him. But then he does have these moments of what’s landing for me as earnestness and sweetness. He is14ish, and that’s a pretty prime age to begin being pretty aggressively self-involved, so I wouldn’t indict him for that too quickly. So the jury’s out for me. I don’t fully dislike him, but I also don’t especially like him, even though I do see some sweetness there. Or maybe he’s just an Eddie Haskell.

Although I’m mostly resisting making comparisons to Wallace’s work, I do have a little trouble not seeing some Avril Incandenza in Fondajane — brilliant and academic, striking, tall, enablingly protective, and at times sort of obnoxiously chirpy and performative.

I’ve found myself in next week’s reading wondering how much I like Belt as an adult (indeed it’ll likely be a theme of my next post), so I’ll be curious to see where you land with respect to Belt as we hit the home stretch.

Was there an earlier moment in the book where the paw of the Cure was also described as a triangle? I was sure I read a part that ended with a description of the foot as a triangle followed by the three dots. But now I cannot find it.

Maybe in the bit at the pizza place with a triangle of claw in Lotta’s cleavage?

I think there was a mention of Blank’s…footprint, more or less, being a triangle of dots, because he’s got three legs, right? Something about him being a tripod, and the dots from each of his “pods” forming the shape of a triangle.

I think I speculated that the dots might represent Blank’s tripodic stance, but I don’t think that was given in the book (but it might’ve been and I internalized it).

Here’s the trouble I’m having in figuring out how much I like (or don’t) Triple-J: This book has a base template for human beings that already gives me a little trouble. None of them talk like anyone I’ve ever met (although it’s possibly fair to say that they talk like people think), but they do all kind of talk alike (even if the Yachts have a different inflection on it), and it’s varying degrees of off-putting. So to think of how much I like a character, I have to tare for that fundamental friction I have with all of them. For instance—I like Fon, overall, I think! But I could sure do without the conversational mise en abyme about how Belt’s hot for her and she knows that and she’s flattered and they have to talk about it so they can not talk about it etc. etc.

All that said, I think I do, more or less, like Triple-J, but I also definitely want more from him. I think he’s got basically good instincts about wanting to be a more productive member of society than the bare minimum his privilege would let him get away with. And god knows I had some things to say at that age that are embarrassing to look back on. We’ll see, I suppose.

I think of the Yachts as like the roving gang in A Clockwork Orange (I’ve seen the movie, never read the book), with their cant and their dress and their cruelty. I love how they talk while also finding it bizarre (clearly intentionally so). Like I can’t quite tell whether they take their manner of speaking seriously or not. Maybe it’s in a weird way a sort of substitute for text speak among kids today (but in the absence of instant text messaging technology). I find it charming and sort of off-key and very funny.

The only thing I know about Proust is the Monty Python’s Flying Circus Summarize Proust competition (which if you haven;t seen, will surely make you laugh). So this was enlightening and makes me maybe want to read Proust (despite your snooze alert).

As you were talking about Belt as author of this book, it made me think..does this book of belt’s have a title? I assume it’s not Bubblegum. In fact, Bubblegum seems like a weird title for this book in general (yes, the scent, but there must be some other reason for it).

Talking about Proust also reminded me that Trip thinks Michel Foucault is Marcel Marceau at first…maybe a nod?

Speaking if Prousts’s text, this sure makes English seem plain and boring no?:

….she smoothed away, as she read, any harshness or discordance in the tenses of verbs, endowing the imperfect and the preterite with all the sweetness to be found in generosity,

Ha, I had never seen that Python sketch.

Regarding the title, I think I’d like to try to remember to loop back to that at the end. The memory of the spat gum and the connection to Mom does seem pretty significant, but there are other little things too. The cures smell like grape bubblegum, for example. I can conjure a very potent gum smell sensory memory that is very nostalgic. And non-visual, non-aural sense memory seems weird to me — a much less frequent memory me at least, and yet somehow also more potent. I’m suddenly pulled back 30+ years to opening pieces of Bazooka bubble gum and reading the little comic, of filling my whole mouth with a wad of Bubble tape, of chewing the wrapper of Cinnaburst, of blowing bubbles with banana flavored Hubba Bubba or Bubbleyum while playing red-rover with neighbors on summer nights. That’s a lot of very powerful sense memory for me at least, tied very directly to bubblegum. I can’t say of course whether Levin has similar associations, but attaching a recollection of childhood so firmly to a pivotal moment in Belt’s adulthood seems like an ok reason to go with Bubblegum for a title.

And then there’s a digression early in the book about the history of bubblegum and why it even became a thing. There was a similar digression about something else later (I forget what — maybe I’m thinking of Gus on hats or handkerchiefs?) that felt very similar. So I wonder if going back at the end of the book and considering all of this together will make it make more sense. But for me, especially as I think about Proust’s book and its consideration of sense memory and childhood, bubblegum seems to fit, though any number of other titles could’ve fit too, of course.