Part Two of the book is called “The Hope of Rusting Swingsets”

So if you thought the swing set murders were not going to be revisited, you’d have been wrong.

Part 2 Section 1 is called “Look at Your Mother.” It concerns Stevie Strumm.

Belt has had a crush on Stevie for a while. She’s the only girl that he can comfortably talk to. Stevie had once given him a mixtape because he liked her Cramps shirt. Stevie, the second youngest Strumm, invited Belt over to destroy their rusted swingset (number ten in his murderous spree). She was babysitting her younger sister while the rest of her family was at a G N’ R show.

The end of the second paragraph promises two events that we haven’t seen and may or may not. He has a vertiginous feeling that he will feel “while dressing at the foot of Grete the grad student’s bed and after reading No Please Don’t‘s first review.”

This swingset murder attracts a large crowd, but is notable for the conversation he has with the swingset. The swingset is grateful that Belt came along. Nobody swings on it anymore, it’s swing is wrapped around the crossbeam. It’s just rusting. The swingset is really down on itself ||I know I’m repellent|| and Belt tries his best to comfort it saying he wants to swing on it one last time.

This event is also significant for a few other things. Jonboat’s driver Burroughs introduces himself for the first time (Jonboat wishes Belt to “break a leg”). Belt is doing this for Stevie, but is aware that she is not watching and then see that she gets a hickie from Jonbaot in his limo.

And the cops arrive.

A bunch of the kids are at the station and they try to figure out who called the cops. Blackie is a suspect (he wasn’t there). Rhino Riggings suggests it was Jonboat (he has a phone in the limo). But the fink was Sally-Jay Strumm, Stevie’s eight-year old sister. She gives no reason but Belt has some ideas. She was brought to the station by her grandfather (a biker with hair dyed blacker than his leathers). The grandfather tells Sally-Jay that “Finking wrecks fun and Finking makes trouble.”

Grandpa has a teardrop tattoo and when he sees Stevie’s hickie he assumed it is police brutality and he stars a brawl.

When Belt’s mother comes to pick him up she is mostly concerned that he wasn’t drinking or taking drugs. She can’t believe he was at a party where people were doing that.

Eventually she asks why he did what he did to the swingset and the story shapes up that Stevie asked him to do it and his mom is happy he likes a girl (even if she throws parties where kids get drunk).

One thing that fascinates me is that the flashbacks are set in 1987. That’s the year I graduated high school. All of the flashbacks are part of my childhood memory, so I can relate almost 100%. But when I think back. If hypothetically this book was written in 1987 and the flashbacks were set in 1957, those flashbacks would be like the dark ages to me. So if you are reading this in high school now, 1987 wasn’t really that long ago. It was just a world without the internet–just like Belt’s world.

I hated family sitcoms–so I played the troubled teen who refused to be pacified… You either aimed for Ferris Beuller [Ferris Beuller’s Day Off] or Dallas Winston [The Outsiders]–which on its own was bad enough–but in the first case you’d end up coming off like Ricky Stratton [Silver Spoons], maybe even Mike Seaver [Family Ties], and in the second case Cockroach [The Cosby Show?] or Boner Stabone [Growing Pains]. By You I mean I. At least for awhile.

My favorite evidence of a different world than ours comes in this hilarious section where Belt is thinking about what a Botimal could actually be. He hasn’t seen one yet, but could you imagine:

A pet that was somehow cuter than a mogwai? One that smelled like candy, spoke and sang, and hatched from an egg you wore on your wrist. A pet of that description that was also a robot? It sounded about as real as genies. As ray-guns, light sabers, X-ray glasses. As pocket-size, voice commendable Game Boys that doubled as camcorders , tripled as calculators, and made long-distance telephone calls.

Fantastic.

Part 2, Section 2 is “Eleventh”

It begins with Belt watching Grandpa Reinhardt Alfons Grandpa Strumm making a statement to the media about the pigs. Then Rory Riley calling him to say he’s a star. Even Wheelatine High School’s own Milo Sorkin called him! They all wanted to know when the next swingset murder would be. But Belt decided not to do any more at least publicly.

Belt wanted to give Stevie a note in school the next day but she wasn’t there. People speculated why she wasn’t in school. But it was also revealed that Grandpa fell off a barstool and died last night.

Blackie and “his aspiring toady, schoolwide chess champ Harold Euwenus mocked Belt: “Why the long face, fuck-ass… Sad about pawpaw.” When Euwenus jokes that her family probably does call him pawpaw because “they’re total white trash,” Blackie says “My family says pawpaw.” And give his toadie what for.

But Stevie isn’t sad about her grandpa dying. “He’s a terrible person. He beat on my dad.” He is a Nazi. in a white supremacist gang called the “Aryan Fuckers.” But guess who is a Jew? Stevie’s mom.

Stevie has seen Belt reading Cat’s Cradle, so she was reading Slaughterhouse-Five, “The only non-board book I’ve read twice.”

There’s a fascinatingly thoughtful section about young love.

Belt says he thinks he’s in love with Stevie and she says she knows. He’s the only boy she ever has real conversations with. It’s a big deal that he tried to understand her. She wishes she wanted to kiss him.

I’ll want to one day, I know that much, but it won’t be til you’re twenty, maybe even twenty-five, because that’s the kind of face you have, the kind I’ll like when you’re a man. Not just me, either. Lots of girls. Which is exactly what sucks. For me, it sucks, I mean. Because the reason you’re into me is I have a certain style and I’m confident about it. Once your face becomes the kind I’ll want to kiss, though, you’ll know a lot of confident styley girls to talk to. I’ll be old news. I’ll be just the same as I am right now, and maybe worse.

This sounds like an insight from experience.

The next swingeset murder was a solitary affair. It was at the Temple house. Their tragic story was a local favorite.

Simon Temple won the state lottery–not the whole pot but enough to buy a BMW and make some household improvements. They had put in a new driveway and garage and just needed to remove the old driveway and carport. Then Simon and his children Tommy and Jessa died in a car crash. The car was driven by Simon’s wife Clare and she survived. She was only driving because she had been an alcoholic but sobered up with Simon’s lottery win. They were at wedding that night and Simon got drunk so Clare drove home and fell asleep at the wheel. She didn’t go out much.

The carport was still there and their swingset was under it. It wasn’t hard to guess the swingset wasn’t happy. Although this swingset was not rusted, because it was under the carport. It just had no hope of very being used again. The swingset has a lengthy conversation with Belt.

It is delusional and believes that it is hallucinating everything, including belt [it’s remarkably sad].

Belt went into the garage across the street and borrowed a long-handled spade.

Belt proceeds to murder the swingset. But when he pauses mid way through, the swingset has second thoughts. What if it can be repurposed. Maybe it doesn’t want to die. Belt tries to reassure the swingset that this is the best recourse, especially now that it is damaged. The last blow didn’t feel so right after all. “It felt like defeat. Or maybe more like a victory I’d rather not have won.”

Then the spade says he ruined its existence. During the murder, Belt broke the spade’s handle. It now has no reason to exist. Belt decides to murder the spade to make it completely dead rather than just broken. He’s about to slam it on the driveway to bend it, when the owner of the spade comes home. Her name is Ms Clybourn. She called Belt’s mom, not the cops, and proves to be very sympathetic to Belt. She gives him Crystal Light and talks nicely to him: “pleasant accents were contagious.”

He talks about Stevie and she commiserates about being alone. says she is too pretty to be alone. She is flattered by him and apologizes for calling his mom–she doesn’t want him to get in trouble. After he describes the murders, she suggests he has anger issues and that’s what Belt runs with. He even tells his mother he thinks it’s anger issues because of Stevie. His mother did not like Ms. Clybourn, calling her a drunk.

They get home and Belt’s father is especially awful. I could quote the whole thing at length, but I’ll truncate to my favorite parts

Belt’s father says he’s acting crazy. But there’s crazy crazy and there’s acceptable crazy. Destroying a swingset is the bad kind. Belt asks what kind of crazy is okay.

The kind that doesn’t last and makes sense… Like for instance, what? Maybe this Stevie likes another boy instead of you? So maybe you–and I’m not saying this is what you should do, but just a for-instance of something that’s the better kind of crazy–maybe you kick his fucken ass a little but. Like in front of her. To show her, and him–

“Stop it,” said my mom.

“I’m not trying to say he should kick this kid’s ass…. I’m telling him that hitting people makes more sense than hitting a swingset. Or a driveway or stealing a shovel. … And don’t get me wrong I’m, not talking about terrorism. I’m not talking about bullying. I’m talking about the targeted hitting of people who deserve it or who seem to deserve it even though you shouldn’t in the end, actually hit them, probably. I mean, unless they seem like they’re gonna hit you, or a girl. And if if that was what you were wishing you were doing when you were hitting that swingset or hitting that driveway–I want you to say so because that would make a lot more sense to me, and then, you know, maybe my fatherly duty is more like I have to teach you how to not be sacred to fight instead of figure out who the best kid-shrink for crazy anger problems is. The most important thing, though–and honey, please stop shaking your head, let me finish, he has to hear this–the important things is that when you were hitting that driveway and hitting that swingset, the important thing is you weren’t wishing you were hitting this girl, this Stevie. You don’t hit girls is the important thing, got it? You don’t even picture it. You picture hitting somebody, you picture a guy, okay? And if you’re so angry that you have to hit someone, you better make sure that someone’s a guy or guess what? I’ll hitting you. … And you will deserve it, Billy. Guys like that–guys who hit girls–those are the worst kind of guys there are. Even wore than guys who kick dogs okay? The only guys who deserve getting hit worse than the one who hit girls are the ones who rape kids, which I don’t even want to get into that with you, into thinking about that. But am I wrong, baby? Don’t tel me I’m wrong.”

“You’re sending him the wrong message he’s a coward…. What he should have been doing is talking to us or crying, Clyde. Crying to us”

“Well I don;t know if that’s true…. Crying about a girl you your parents is–well it’s embarrassing.”

After this huge fight Belt’s mother starts pummeling inans–plates, beer steins.

The section ends with Murder #3. It was at the house of Regis Piper. When he saw the murdered swingset, he thought nothing of it. His wife had read about cults, but he didn’t think that was it. But after grandpa and the Nazi connection came out, Piper went to the cops. Suddenly Belt was a suspect. Belt’s dad talked to a cop named Platzik to try to keep Belt out of trouble. But Platzik had a brother at the Herald and his nephew was Euwenus who’d been a the murder and suddenly its was all over the Herald.

Part 2, Section 3 “Friends” provides a backstory I didn’t necessarily think we were going to get. And wow does it fill in a lot. We even get the origin of Belt’s name: Belt Alton Magnet (although no origin for the Alton yet).

Back to 1987. Basically Belt’s mom sees an ad on the subway (after her car got its second flat tire in as many days) for a study introducing therapy animals to children with psychotic disorders.

This is where he met Dr Calgary Tilly and Dr. Lionel Manx and how he got Blank.

In introducing Belt, Belt’s mother explains that he was named after her Uncle Belt. Well, Uncle Gunther was his name” but no one much liked that–how could they?” Gunther’s older brother was bullying him at a bus stop–was making him sing the Happy Birthday song over and over at the top of his lungs

and a young black woman, who my father always swore was Billie Holiday, though no one ever believed him, she approached the two boys and said to my father, “you’re picking on him now, but just you wait. He’s gonna be a star. Little kid’s got pipes. Boy can belt.” And after that Uncle Gunther was Belt.

He never sang though, because he had stage fright. But when he got to high school, kids thought he was called Belt because he liked to hit people. So kids picked on him and he actually got good at fighting. He took up boxing and lost his stage fright. So then he joined a band. But in his next fight his hearing was damaged which wrecked his voice.

Belt was her favorite Uncle and everyone liked him so Belt’s dad (even though he wasn’t crazy about the name), let her call him Belt (which even his dad agreed was better than Gunther).

Manx asks him about destroying swingsets. The doctor asks why he calls them murders and he says the newspapers called it that. It sounds cooler than “the swingset mercies of the swingset help-outs.”

Belt says he is trying to help them. Belt says he would repair them if he could but he’s terrible with his hands. Plus eh couldn’t promise to save all of the swingsets. He makes an analogy of giving money to a homeless person. That basically you’re giving them money to drink or buy drugs so it’s not really helping them. If you want to help, you should give them a home.

Belt is approved for the study. Manx shows him a series of pets which he says he does not want: puppy, turtle, parrot, snake. He is very interested in the sugar gliders, but then Manx tries to sell him on these new items, called Botimals. Manx has no visuals, just a sales pitch. It’s hard to sell a thing that no one has heard of over and adorable sugar glider, but he says they are cuter than Gremlins. This gets Belt (and Belts mom) excited about the idea. So he lets Belt try out the Botimal for a week.

There’s a kind of throwaway section that caught my attention and I wondered if it was a hint that will lead to something ulterior.

Graham&Swords sponsored this study. Manx isn’t sure why. Belt’s mom asks if Graham&Swords are the “we do dishes right” brand. Manx says that indeed it is. But home appliances barely account for a tenth of their business. The majority of their profits actually comes from armaments, though soon I bet it’ll come from Botimals.

Is there going to be some kind of military component to the Botimals?

So Belt has the unhatched Blank in his room.

There’s an example of an inan expressing happiness toward Belt. His swivel chair thanked him for when he occasionally rolled around the room ||Generally speaking, we are vastly underutilized as modes of short-range transport.||

Belt has been stealing Quills from his parents ever since his mom yelled at him for asking for one. He always knew he wanted to smoke. But much of the reason was because he wanted to be a writer and knew his life up until now wouldn’t provide much material. Whereas staring to smoke, “a thing that impressed me as a sign of character” could supply him with a moment worth writing about.

Then he started smoking with Stevie behind the dumpsters. He brought Quills and his Botimal to school. He showed her the egg, but when she asked if she could hold it, he came up with a genius excuse He told her it was a an Indian agate–like a mood ring. There was oil or gas inside and he couldn’t let anyone else touch because his skin caused it to from shapes symbolic of his spirit or something. She thought it was bullshit but let it slide.

When Blank finally hatches, it emitted a sequence of schwas: “ǝ ǝ,” it said. He blew on it; it sneezed and got its name.

The next morning his father fed Kerblankey a diced onion dusted in cayenne. Belt can’t determine his motivation, but Clyde is pretty much a dick. Blank strangled, thrashed and panicked until Belt taught him to spit.

His father apologized. Then he said the way it was singing he was having an “over-kissy grammy moment. I just want to squeeze it. Eat it right up.”

During this section Belt’s mom tells him that she always anthropomorphized animals-in a way that she felt was unhealthy. She connects this to his inans. She says she understands how hard it will be to resist them, but she asks him to promise to never hurt an inanimate object again.

Belt brought Blank to school the next day to show Stevie. She finds it adorable, but is nervous because she just wants to squeeze it. Belt doesn’t feel that way.

Then Rory Riley and Jonboat happen upon them. Stevie thought that Belt and Jonboat could be friends. But the boys walk in on them looking at Blank and they get really handsy. Belt punches Rory. Jonboat is cool about it though and calms everyone down. Belt tells everyone it’s a it’s a sugar glider.

From then on, kids didn’t bother him, they were respectfully distant. Perhaps it was because

I was (or at least had been) all messed up Troubled. Off. Lacing up my rhinestoned shirt in Vegas.

I have never heard this expression before. It’s vivid and wonderful, but so puzzling. I looked up the phrase online and found literally one entry. It is for a memorial service.

Wear any bling you have and any bright colored scarves or hats. If you bought a boa or a rhinestone shirt in Vegas or New Orleans, please wear it because my mother would have appreciated it.

It doesn’t help, but it is fascinating.

Part 2, Section 4 is “Applied Behavioral Science.” This final section for the week is all about Belt’s group study program. Essentially, if he goes through with this study for sixteen weeks, they will give him the animal and pay for his therapy. Belt says that he felt that Graham&Swords were pretty great to him because he dropped out early but they let him keep Blank and paid for his therapy anyway.

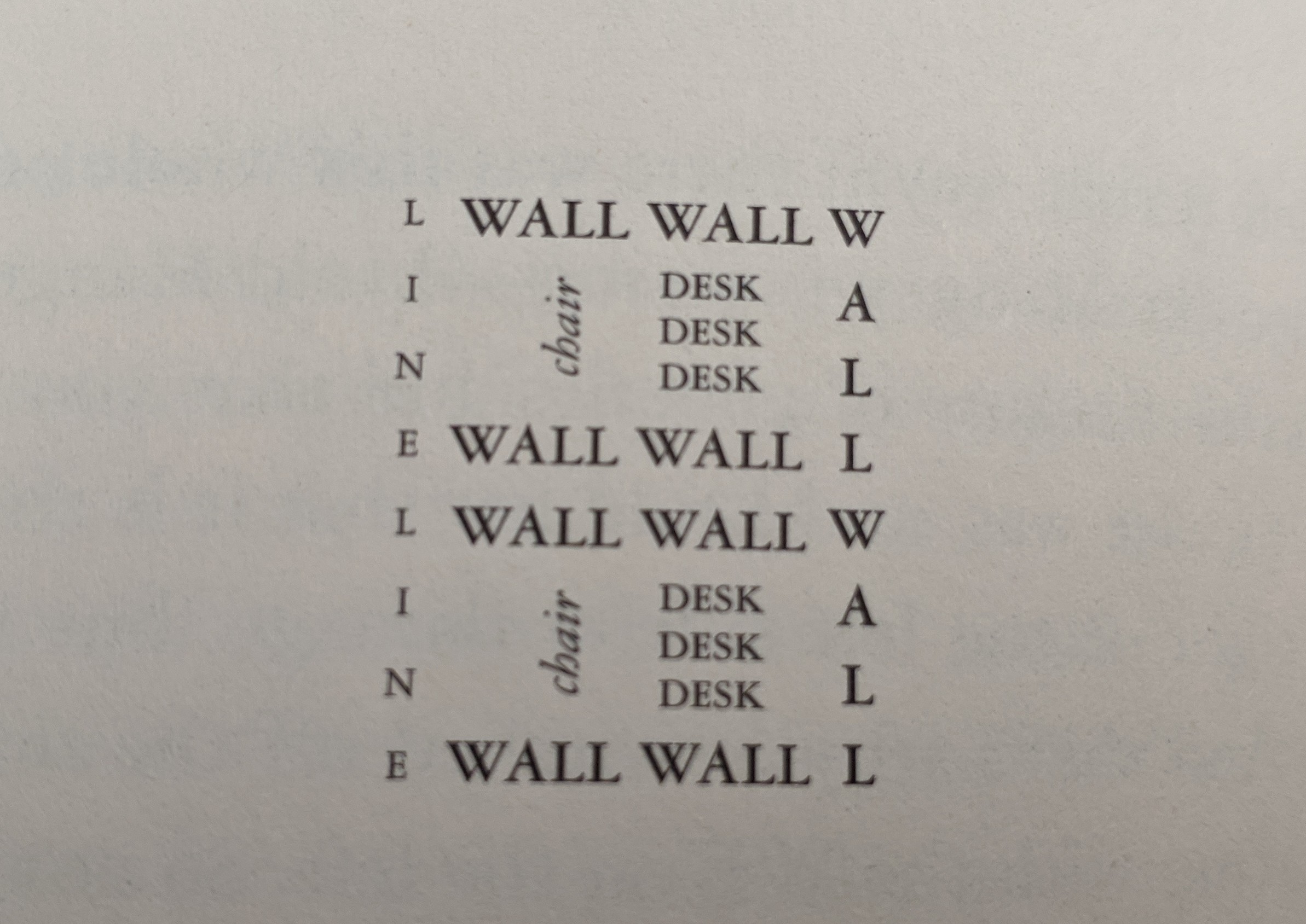

There’s a grad student named Abed (which makes me think of Community). We see the questionnaires that belt [B.A.M.] was supposed fill out before and after each session. Mostly the children have group activities where they interact and are observed. He says most of the kids weren’t really noteworthy, Belt described them playing truth or dare. Most of the kids took truth and deadpanned answers to “personal” questions. But the dares hey gave were either impossible “jump out the window and fly” or like this: “Fart really loud while running in place like you’re running from the fart you did and shout how you love it.”

But he did meet three notable children.

James is a boy with a ferret called Screwball. This boy has a lazy eye is very concerned with whether he thinks people are a retard or if they think he is a retard. He says he’s a hugger, but he notes, “If you have to be a hugger you have to ask permission.”

James is a font of inappropriate language. I often marvel a the words that Levin conjures.

“That’s how its supposed to be. Poontangy haze, better lays and later days, Belt!”

“James please,” said his mom.

“Pleasey von Sleazy and a bottle of redrum.”

But James has got nothing on Bertrand who greets Belt thusly:

Five in a night makes a happy and healthy twenty-fucken-eight, you cocksucking, cockfucking son of a cunt.”

Belt says Bertrand is Sergeant Harmanesque (the yelling sergeant from Full Metal Jacket).

Bertrand calls Belt “Suspendersed”(which is hilarious) and then introduces him to his gecko Mikeylikey.

This is also where he meets Lisette.

Technically, he first met her on his way to meet the doctors. They walked towards each other in the hallway and the girl slammed into him and said “Excuse me, excuse me.” Her mom apologized by Belt thought it was funny.

Lisette was assigned to his group. She refused to bring her pet (she was the sole non-compliant female). He was intrigued but intimidated by her. He believed that he was still mourning Stevie and didn’t want to switch his focus too soon, as if it invalidated his feelings. So he tried to avoid her. Until she started playing footsie (aggressive footsie) with him, repeating the excuse me joke. She makes up an elaborate story about how she got scars saving a bunny from afire. The story seemed fake because first there were two and then there were three but it was all a test to see how Belt would react to her lies.

I don’t know how much these other children will play into the next section. I assume we’ll learn why belt left the study, but the preponderance of children with “problems” is certainly an obvious component to the story.

Lisette talks with him about the inans. She has some intriguing ideas. She asks if all the voices are male. They are. Why? He doesn’t know. She asks him to talk to her glove and he says that clothes never really talk to him. He posits that are shy, but Lisette counters that maybe they are girls and girls don’t talk to him. Indeed, maybe most things are girls and that’s why you only wind up talking to some things.

He repeats what his father said about maybes:

“Maybe’s a shrug. A shrug and a dodge. Maybe’s the sound second thoughts make.”

“That’s the single saddest thing I’ve heard this year. What a disappointment. You sound like somebody’s dumbfuck father.”

Perhaps the Inans stem from his inability to talk to girls?

As the section ends, Manx gives Belt a prototype Cure Sleeve (the one he still has). Manx really seems to have taken to Belt or there is something about Belt that makes him think he is perfect for a Botimal.

Abed also gives the news that his mother collapsed and is in the hospital.

Abed makes a hilariously inappropriate and botched attempt at referencing Bugs Bunny.

Evidently Belt’s mother was trying to downplay how serious it was that she had fallen down. Abed found her on the ground and

She widened her eyes, looking deeply into mine, and plainly stated, “Ah-buh-dee-ah-buh-dee-ah-buh-dee, that is all there is folks.”

“Like Porky Pig?” I said. It didn’t sound like her. Or Porky Pig.

“No!” Abed said. “I have made a mistake. That was my response to her joke. What she said was, “It appeared as though I made an incorrect turn at Albuquerque, New Mexico.”

Abed seems to downplay the seriousness, but when belt’s grandma arrives she says it is indeed serious and that’s why she’s there.

She clearly has no tolerance for any of this psychology mumbo jumbo. She say that Belt’s father had imaginary friends too.

He would try to introduce me. Did I pretend that I saw them? I did not pretend I saw them. I did not pretend to believe he saw them. And guess what happened. He stopped pretending to see them.

Maybe that’s why he’s mean to her over the phone.

I really didn’t expect much backstory in this novel for some reason. It seemed like it would be all forward-looking. I’m very curious now how much more we’ll see of 1987. And if we’ll meet Grete the grad student.

♦

♦ ♦

Incidentally, I co-posted this on my own site which includes a “Soundtrack” for each post. All of the posts for Bubblegum will “feature” bubblegum pop songs. This week’s is Ohio Express with “Chewy Chewy.”.